Megali Idea

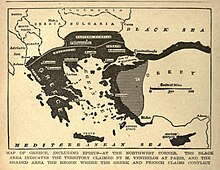

The Megali Idea (Greek: Μεγάλη Ιδέα, romanized: Megáli Idéa, lit. 'Great Idea')[1] is a nationalist[2][3] and irredentist concept that expresses the goal of reviving the Byzantine Empire,[4] by establishing a Greek state, which would include the large Greek populations that were still under Ottoman rule after the end of the Greek War of Independence (1821–1829) and all the regions that had large Greek populations (parts of the southern Balkans, Anatolia and Cyprus).[5]

The term appeared for the first time during the debates of Prime Minister Ioannis Kolettis with King Otto that preceded the promulgation of the 1844 constitution.[6][7] It came to dominate foreign relations and played a significant role in domestic politics for much of the first century of Greek independence. The expression was new in 1844 but the concept had roots in the Greek popular psyche, which long had hopes of liberation from Ottoman rule and restoration of the Byzantine Empire.[6]

Πάλι με χρόνια με καιρούς,

- πάλι δικά μας θα 'ναι!

(Once more, as years and time go by, once more they shall be ours).[8]

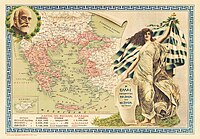

The Megali Idea implies establishing a Greek state, which would be a territory encompassing mostly the former Byzantine lands from the Ionian Sea in the west to Anatolia and the Black Sea to the east and from Thrace, Macedonia and Epirus in the north to Crete and Cyprus to the south. This new state would have Constantinople as its capital: it would be the "Greece of Two Continents and Five Seas" (Europe and Asia, the Ionian, Aegean, Marmara, Black and Libyan Seas). If realized, this would expand modern Greece to roughly the same size and extent of the later Byzantine Empire, after its restoration in 1261 AD.

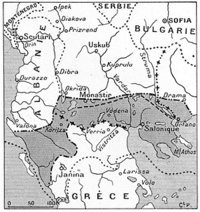

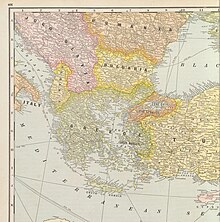

The Megali Idea dominated foreign policy and domestic politics of Greece from the War of Independence in the 1820s through the Balkan wars in the beginning of the 20th century. It started to fade after the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922), followed by the population exchange between Greece and Turkey in 1923. Despite the end of the Megali Idea project in 1922, by then the Greek state had expanded four times, either through military conquest or diplomacy (often with British support). After the creation of Greece in 1830, it acquired the Ionian Islands (Treaty of London, 1864), Thessaly (Convention of Constantinople (1881)), Macedonia, Crete, (southern) Epirus and the Eastern Aegean Islands (Treaty of Bucharest), and Western Thrace (Treaty of Neuilly, 1920). The Dodecanese were acquired after the Second World War (Treaty of Peace with Italy, 1947).

A related concept is enosis.

Fall of Constantinople

[edit]

The Byzantine Empire was Eastern Roman in origin and was called the "Roman Empire" by its inhabitants, though often not by the Latin West, which regarded it as Greek. After its fall, Hieronymus Wolf popularized the usage of "Byzantium". An informal cultural division had existed within the Roman Empire for centuries. Although Latin was the official language of the empire, Greek was the lingua franca in the East and was regularly used alongside Latin in official business. The division of the Empire following the death of Emperor Theodosius in AD 395 added a formal political layer to the informal cultural division. Following the adoption of Christianity in the 4th century, Greek was also the dominant liturgical language, as exemplified by the fact the New Testament was written in Greek. These factors ultimately led to Greek replacing Latin as the official language in AD 620.

Byzantium held out against numerous invasions over the centuries and during the 10th and early 11th centuries managed to reclaim considerable territory in the Balkans, Anatolia and to a lesser extent Syria. The Turkish invasion of the mid to late 11th century however greatly weakened the Empire and, although it partially recovered under the Komnenos dynasty, it never managed to regain control of the Anatolian interior, cutting the empire off from a valuable source of manpower and tax revenue. In 1204 Constantinople was besieged and sacked during the Fourth Crusade and became the Capital of what has come to be known as the Latin Empire, a French dominated crusader state, until it was liberated by the Empire of Nicaea, the Byzantine state in exile, in 1261. However, Byzantine strength would rapidly diminish towards the end of the 13th century and evaporated almost entirely during the 14th century, to the extent that by 1400 little remained of the Empire except Constantinople, the city’s immediate surroundings and some small territories in modern-day Greece. In 1453 the Ottoman Turks besieged and captured Constantinople officially marking the end of the Roman Empire and also the end of Greek predominance in the city; although it would continue to have a considerable Greek speaking population and the Patriarch of Constantinople continued to reside in the city.

Greeks under Ottoman rule

[edit]

- Bulgars and Turks

- Greeks

- Armenians

- Kurds

- Lazes

- Arabs

- Nestorians

Under the millet system which was in force during the Ottoman Empire, the population was classified according to religion rather than language or ethnicity. Orthodox Greeks were seen as part of the millet-i Rûm (literally "Roman community") which included all Orthodox Christians, including beside Greeks also Bulgarians, Serbs, Vlachs, Slavs, Georgians, Romanians and Albanians, despite their differences in ethnicity and language and despite the fact that the religious hierarchy was Greek dominated. It is not clear to what extent one can speak of a Greek identity during those times as opposed to a Christian or Orthodox identity.[9] In the late 1780s, Catherine II of Russia and Joseph II of Austria intended to reclaim the Byzantine heritage and restore the Greek statehood as part of their joint Greek Plan.

During the Middle Ages and the Ottoman period, Greek-speaking Christians identified as Romans and thought of themselves as the descendants of the Roman Empire (including the medieval Eastern Roman Empire). The term Roman was often interpreted as synonymous with Christian throughout Europe and the Mediterranean during this time. The terms Greek or Hellene were largely seen by Ottoman Christians as referring to the ancient pagan peoples of the region. This changed during the late stages of the Ottoman Empire and the emergence of the Greek independence movement.[10][11]

For much of the period of the Tourkokratia, the Russians were viewed by the Greeks as the xanthon genos, a fair-haired race and the sole Orthodox power that would liberate Constantinople from the Ottomans.[5] The Greek legend of the xanthon genos eventually liberating Constantinople was also referenced in the 15th-century Tale on the Taking of Tsargrad, which itself was widely circulated in Russia between the 16th and 18th centuries.[12][13]

Greek War of Independence and later

[edit]"The Kingdom of Greece is not Greece; it is merely a part: the smallest, poorest part of Greece. The Greek is not only he who inhabits the Kingdom, but also he who inhabits Ioannina, Salonika or Serres or Adrianople or Constantinople or Trebizond or Crete or Samos or any other region belonging to the Greek history or the Greek race... There are two great centres of Hellenism. Athens is the capital of the Kingdom. Constantinople is the great capital, the dream and hope of all Greeks."

After the Greek War of Independence ended in 1829, a new southern Greek state was established, with assistance from the British Empire, Kingdom of France, and Imperial Russia. However, this new Greek state under John Capodistrias after the Greek War of Independence was, with Serbia, one of the only two countries of the era whose population was smaller than the population of the same ethnicity outside its borders; most ethnic Greeks still resided within the borders of the Ottoman Empire. This version of Greece was designed by the Great Powers, who had no desire to see a larger Greek state replace the Ottoman Empire.

The Great Idea embodied a desire to bring all ethnic Greeks into the Greek state, and subsequently revive the Byzantine Empire; it applied specifically to the Greeks in Epirus, Thessaly, Macedonia, Thrace, the Aegean Islands, Crete, Cyprus, parts of Anatolia, and the city of Constantinople (which would replace Athens as the capital).

When the young Danish prince Wilhelm Georg was elected king in 1863, the title offered to him by the Greek National Assembly was not "King of Greece", the title of his deposed predecessor, King Otto; but rather "King of the Hellenes". Implicit in the wording was that George I was to be king of all Greeks, regardless of whether they then lived within the borders of his new kingdom.

The first additional areas to be incorporated into the Kingdom were the Ionian islands in 1864, and later Thessaly with the 1878 Treaty of Berlin.[15]

Revolts, Cretan crisis and Greco-Turkish War (1897)

[edit]

In January 1897, violence and disorder were escalating in Crete, polarizing the population. Massacres of the Christian population took place in Chania and Rethimno. The Greek government, pressured by public opinion, intransigent political elements, extreme nationalist groups (e.g. Ethniki Etairia) and with the Great Powers reluctant to intervene, decided to send warships and personnel to assist the Cretans. The Great Powers had no option then but to proceed with the occupation of the island, but they were too late. A Greek force of 1,500 men had landed at Kolymbari on 1 February 1897, and its commanding officer, Colonel Timoleon Vassos, declared that he was taking over the island "in the name of the King of the Hellenes" and that he was announcing the union of Crete with Greece. This led to an uprising that spread immediately throughout the island. The Great Powers finally decided to land their troops and stopped the Greek army force from approaching Chania. At the same time their fleets blockaded Crete, preventing both Greeks and Turks from bringing any more troops to the island.

The Ottoman Empire, in reaction to the rebellion of Crete and the assistance sent by Greece, relocated a significant part of its army in the Balkans to the north of Thessaly, close to the borders with Greece. Greece in reply reinforced its borders in Thessaly. However, irregular Greek forces and followers of the Megali Idea acted without orders and raided Turkish outposts, leading the Ottoman Empire to declare war on Greece; the war is known as the Greco-Turkish War of 1897. The Turkish army, far outnumbering the Greek, was also better prepared, due to the recent reforms carried out by a German mission under Baron von der Goltz. The Greek army fell back in retreat. The other Great Powers then intervened and an armistice was signed in May 1897. The war, however, only ended in December of that year.

The military failure in the Greco-Turkish war cost Greece small territorial losses along the border line in northern Thessaly, and a large sum of financial reparations that wrecked Greece's economy for years, while giving no lasting solution to the Cretan Question. The Great Powers (Britain, France, Russia, and Italy) in order to prevent future clashes and trying to avoid the creation of a revanchist climate in Greece, imposed what they thought of as a lasting solution; Crete was proclaimed an autonomous Cretan State. The four Great Powers assumed the administration of Crete; and, in a decisive diplomatic victory for Greece, Prince George of Greece (second son of King George I) became High Commissioner.

Early 20th century

[edit]Balkan Wars

[edit]

A major proponent of the Megali Idea was Eleftherios Venizelos, under whose leadership Greek territory doubled in the Balkan Wars of 1912–13 — southern Epirus, Crete, Lesbos, Chios, Ikaria, Samos, Samothrace, Lemnos and the majority of Macedonia were attached to Greece. Born and raised in Crete, in 1909 Venizelos was already a prominent Cretan and had influence in mainland Greece. As such, he was invited after the Goudi coup in 1909 by the Military League to become Prime Minister of Greece. Venizelos pressed forward a series of reforms in society, as well as the military and administration, which helped Greece succeed in its goals during the Balkan Wars.

World War I

[edit]

Following the Greek gains in the Balkan Wars, the Ottomans began to persecute ethnic Greeks living in the Empire, which led to ethnic cleansing in the Greek genocide. This persecution continued into World War I when the Ottomans declared for the Central Powers on late 1914. Greece remained neutral until 1917 when they joined the Allies. Refugees reports of Turkish atrocities as well as the Allied victory in World War I seemed to promise an even greater realization of the Megali Idea. Greece gained a foothold in Asia Minor with a protectorate over Smyrna and its hinterland. Following 5 years of Greek administration, a referendum was to be held to determine whether the territory would revert to Ottoman control or join Greece. Greece also gained the islands of Imbros and Tenedos, Western and Eastern Thrace, the border then drawn a few miles from the walls of Constantinople.

Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922)

[edit]

Greece's efforts to take control of Smyrna in accordance with the Treaty of Sèvres were thwarted by Turkish revolutionaries, who were resisting the Allies. The Turks finally prevailed and expelled the Greeks from Anatolia during the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922) (part of the Turkish War of Independence). The war was concluded by the Treaty of Lausanne which saw Greece cede Eastern Thrace, Imbros, Tenedos and Smyrna to the nascent Turkish Republic. To avoid any further territorial claims, both Greece and Turkey engaged in an "exchange of populations": During the conflict, 151,892 Greeks had already fled Asia Minor. The Treaty of Lausanne moved 1,104,216 Greeks from Turkey,[16] while 380,000 Turks left the Greek territory for Turkey. The transfers ended any further appetite for pursuing the concept of a Greater Greece and ended the 3000 year Greek habitation of Asia Minor. Further population exchanges occurred after World War I, including 40,027 Greeks from Bulgaria, 58,522 from Russia (because of the defeat of the White Army led by Pyotr Wrangel) and 10,080 from other lands (for example Dodecanese or Albania), while 70,000 Bulgarians from Thrace and Macedonia had moved to Bulgaria.[17] From the Bulgarian refugees ca. 66,000 were from Greek Macedonia.[18]

The immediate reception of refugees to Greece cost 45 million francs, so the League of Nations arranged for a loan of 150 million francs to aid settlement of refugees. In 1930, Venizelos even went on an official visit to Turkey, where he proposed that Mustafa Kemal be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

The Greek novelist Yiorgos Theotokas described the psychological impact of the defeat of 1922:

"For a short time, while the Treaty of Serves ran its joyful but uncertain course, it seemed to them that the...long-buried hopes of their ancestors were to be fulfilled. But the terrible summer of 1922 came all too soon. From the hermitage of Arsenios they watched, tense with anxiety, the daily unfolding of the national tragedy, the last desperate efforts of the Royalist Governments of Greece to save the situation, the failure of King Constantine's attempt to take Constantinople, and the final Catastrophe.

In mid-August Mustapha Kemal broke through the Greek front and the Greek army, exhausted by ten years of warfare and the privations of the Asia Minor campaign, was vanquished in two weeks. The Turks, advancing rapidly, recaptured in quick succession Afion-Karahisar, Eski-Shehir, Kiutahia, Brussa, Oushak—and then Smyrna! Once again the banners of Islam floated proudly, tauntingly, over the Aegean coast opposite Chios and Mytilene. The whole of Ionia was in flames. Slaughter and pillage descended on the smiling city of Smyrna and in a few short days turned it into a ruin...As day succeeded day, Greece seemed to have become paralyzed, to have lost all will, all ability to resist the blows of fate. The swiftness of the catastrophe completely overwhelmed the State, flooded as it was by the thousands of fleeting soldiers and refugees who sought shelter on the Greek coasts.The nation was plunged into deep despair...

Greece had lost her big gamble and had been uprooted from Asia Minor. St. Sophia remained in the hands of the Moslems. The brilliant plans of 1918 were mocking visions, hallucinations, dreams. And the return of reality was truly heartbreaking. The tale of the years was not yet told, then, the historic hour, the fulfillment of the Great Idea, the moment they had longed for with such faith and such anxiety for five tortured, bloody centuries, had not yet come! It was all a lie!"[19]

World War II, annexation of Dodecanese and Cyprus dispute

[edit]

Although the Great Idea ceased to be a driving force behind Greek foreign policy, some remnants continued to influence Greek foreign policy throughout the remainder of the 20th century.

Thus, after his coup d'état of 4 August 1936, Ioannis Metaxas proclaimed the advent of the "Third Hellenic Civilization", similar to Adolf Hitler's Third Reich (influenced by pan-Germanism).[20] The attack by Italy from Albania and the Greek victories enabled Greece to conquer, during the winter of 1940–1941, parts of southern Albania (Northern Epirus, as it is identified by Greeks) which were administered as a province of Greece for a short time until the German offensive of April 1941.

The occupation, resistance and the civil war initially put the Great Idea in the background. Nevertheless, another very good diplomatic performance by the Greek side at the Paris Peace Conference, 1946 secured a further enlargement of Greek territory, in the form of the Dodecanese Islands, despite the very strong opposition of Vyacheslav Molotov and the Soviet delegates.[21]

The British colony of Cyprus became the "apple of discord" between the two countries, putting an end to the positive Greco-Turkish relations that had existed since the Kemal-Venizelos agreement in the 1930s. In 1955, a Greek army colonel of Greek Cypriot origin, George Grivas, began a campaign of civil disobedience whose purpose was primarily to drive the British from the island, then move for Enosis with Greece. The Greek prime minister, Alexandros Papagos, was not unfavourable to this idea.[citation needed] There was increasing polarisation of opinion between the dominant Greek population and the minority Turks.[citation needed]

The problems in Cyprus affected the continent itself. In September 1955, in response to the demand for Énosis, an anti-Greek riot took place in Istanbul. During the Istanbul Pogrom 4,000 stores, 100 hotels and restaurants and 70 churches were destroyed or damaged.[22] This led to the last great wave of migration from Turkey to Greece.

The Zürich Agreement of 1959 culminated in independence of the island with Greece, Turkey and UK as guarantee powers. The inter-ethnic clashes from 1960 led to the dispatch of a peacekeeping force of the United Nations in 1964.

The Cyprus issue was revived by the dictatorship of the colonels, who presented their April 21, 1967, coup d'état as the only way to defend the traditional values of what they called the "Hellenic-Christian Civilization".

Brigadier General Ioannidis arranged, in July 1974, to overthrow Cypriot President Archbishop Makarios, and proceed with Enosis (union with Greece).[citation needed] This led to Turkey invading the island in response, with the expulsion of Greek Cypriots in areas controlled by Turkey, and the flight of Turkish Cypriots from the south. In 1983, the north declared independence and to this day, Turkey is the only country that recognizes Northern Cyprus.

Attempted revival by Golden Dawn

[edit]The ultra-nationalist Golden Dawn party, which had electoral support from 2010 to 2019, supports the Megali Idea,[23] with party leader, Nikolaos Michaloliakos stating:

For two thousand years, the Jews would say a wish during their festivals, "next year in Jerusalem", and ultimately after many centuries they managed to make it a reality. So I too conclude with a wish: Next year in Constantinople, in Smyrna, in Trebizond!

— [23]

Michaloliakos criticized Thessaloniki mayor Yiannis Boutaris for wanting to name a street after Atatürk, who was born in the city when it was still part of the Ottoman Empire.[24][25] In January 2013, a group of Golden Dawn supporters attacked the car of Turkish consul-general Osman İlhan Şener and hurled insults at Atatürk, during an anti-Turkey protest in Komotini.[26]

Mihaloliakos has also called for the "liberation"[citation needed] of Northern Epirus. Golden Dawn and its former Cypriot counterpart ELAM support enosis.

In 2015, close to 100 Golden Dawn members and leaders were arrested on a range of charges, including murder and racketeering. In 2019, the party's level of support, slumped to less than 2%. In October 2020, most of Golden Dawn's leadership was convicted, including Michaloliakos. As of 2023, the party, which never enjoyed electoral support above 10% of the popular vote, now has no remaining members in either the Hellenic or European Parliament.[27]

See also

[edit]- Greek diaspora

- Northern Epirus

- Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus

- Occupation of Constantinople

- Irredentism

- Zone of Smyrna

- Republic of Pontus

- Georgios Grivas

- Foreign relations of Greece

- Succession of the Roman Empire

References

[edit]- ^ Mateos, Natalia Ribas. The Mediterranean in the Age of Globalization: Migration, Welfare & Borders. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 9781412837750.

- ^ Miller, James Edward (2009-02-01), "Introduction: Manifest Destiny Meets the Megali Idea", The United States and the Making of Modern Greece, University of North Carolina Press, pp. 1–22, doi:10.5149/9780807887943_miller.6, ISBN 9780807832479, retrieved 2022-10-21

- ^ A., Jenkins, Mary (1994). To megali idea - dead or alive? : the domestic determinants of Greek foreign policy. Naval Postgraduate School. OCLC 35675237.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Roumen Daskalov, Tchavdar Marinov, Entangled Histories of the Balkans - Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies; BRILL, 2013; ISBN 900425076X, p. 200.

- ^ a b Clogg 2002, p. 60.

- ^ a b History of Greece Archived 2019-06-07 at the Wayback Machine Encyclopædia Britannica Online

- ^ Clogg 2002, p. 244.

- ^ D. Bolukbasi and D. Bölükbaşı, Turkey And Greece: The Aegean Disputes, Routledge Cavendish 2004

- ^ Koliopoulos, John S.; Veremis, Thanos (2007). Greece: The Modern Sequel. C Hurst & Co Publishers Ltd.

- ^ Honing, Matthias; Vogl, Ulrik; Moliner, Olivier, eds. (31 May 2012). Standard Languages and Multilingualism in European History. John Benjamins. p. 163. ISBN 9789027273918.

- ^ Zacharia, Katerina, ed. (2008). Hellenisms: Culture, Identity, and Ethnicity from Antiquity to Modernity. Ashgate Publishing. p. 240. ISBN 9780754665250.

- ^ Terras, Victor (1 January 1985). Handbook of Russian Literature. Yale University Press. p. 302. ISBN 978-0-300-04868-1.

- ^ Aberbach, David (13 September 2016). National Poetry, Empires and War. Routledge. pp. 145–150. ISBN 978-1-317-61810-2.

- ^ Smith M., Ionian Vision, (1999), p. 2

- ^ Clogg 2002, pp. 67–71.

- ^ André Billy, La Grèce, Arthaud, 1937, p. 188.

- ^ The Treaty of Neuilly-sur-Seine led to an exchange of 50,000 Greeks for 70,000 Bulgarians between the two countries. For more see: Rutsel Silvestre, J. Martha; The Financial Obligation in International Law, Oxford University Press, 2015; ISBN 0191055956, p. 70.

- ^ "The second wave of Bulgarian refugees took place in the 1920s, following the signing of the Neilly Treaty (1919) concerning the so-called "voluntary" exchange of population between Greece and Bulgaria. Of them 66,126 people from Greek Macedonia." For more see: Victor Roudometof, Collective Memory, National Identity, and Ethnic Conflict: Greece, Bulgaria, and the Macedonian Question; Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002 ISBN 0275976483, p. 97.

- ^ Kaloudis, George "Ethnic Cleansing in Asia Minor and the Treaty of Lausanne" p.59-89 from International Journal on World Peace, Volume 31, No. 1, March 2014 p.83-84

- ^ R. Clogg, p. 118.

- ^ K. Svolopoulos, Greek Foreign Policy 1945–1981, p. 134.

- ^ R. Clogg, p. 153.

- ^ a b Μιχαλολιάκος: Του χρόνου στην Κωνσταντινούπολη, στην Σμύρνη, στην Τραπεζούντα…. Stochos (in Greek). 31 December 2012. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ^ "Greek far-right leader vows to 'take back' İstanbul, İzmir", Today's Zaman, 15 June 2012, archived from the original on 3 November 2013, retrieved 12 September 2012

- ^ "Greek 'Führer' vows to 'take back İzmir' after Istanbul". Hürriyet Daily News. 15 June 2012. Archived from the original on 25 December 2020. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- ^ "Yunanistan'da Türk konsolosun aracına saldırı" (in Turkish). NTVMSNBC. Archived from the original on 12 January 2013. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- ^ Gatopoulos, Derek; Becatoros, Elena (7 October 2020). "Greek court rules Golden Dawn party criminal organization". Associated Press. Retrieved January 3, 2020.

Sources

[edit]- Clogg, Richard (20 June 2002). A Concise History of Greece. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00479-4.